Social mobility in Medieval society and The Three Estates.

The middle ages is traditionally seen as a time in which an individual’s social status was a mark for life, unshakable but for legendary stories of hero’s or revolutionaries breaking the molds of their unjust society. However the truth of the solidity of these roles is a more debatable mater when one cares to scratch the surface of this long handed down view. We look to the Middle Ages with a modern eye, often leading to a narrow interpretation of a system that was not without its twists therefore it is important to take a step back in order to make an analytical view on just how useful this application can be in understanding the middle ages.

The Three estates are separated into basic sections vital to the medieval mind-set; those who pray (Oratones); those who fight (Bellatones) and those who work (Labortones). These estates, in theory, carried a social hierarchy with them. In a world where an individual’s very birth was believed to be God’s intention it was therefore believed that it was their duty and expectation to fulfil the role allotted to them in life in both actions and social conventions. The concept therefore treads the lines of the hotly debated idea of a feudal system. The Feudal system as we know it is a creation of the 17th century writers rather than a term that was used by the people of the time. Feudal law was brought about by 12th century Italian lawyers as a means for as a means for fief holder to exercise judicial power, making it a more akin to a legal statement over a solid social ruling. The problem stands that this is therefore a very bold convention to impose on the Middle Ages at large, especially when we consider that fief holding was a rare occurrence. Feudalism in turn comes with a negative context to the modern mind set; viewing it as unjust and barbaric at worse. The Ad hoc foundations of this world view are at best understandable in the sense of a divinely ordained birth right but as frequently brought up by those who have argued how solid the concept is that there were even more layers to these ‘three’ standings. The first challenges to the idea of the three estates as a method of addressing the social system of the medieval world come from as early as the 12th century. French Scholar Peter the Chanter would still use the basic theory yet expand it to divide the ‘Labourtones’ into sub categories such as ‘Peasants’, ‘Artisans’ and ‘The poor’.

It is important to note that as the middle ages took shape peasant slavery was whittling down to a nearly non-existent margin in Europe. This lead to an increase in serfdom, meaning a man could be freemen who earned a wage, however where tied a domain as tenants whom would pay via rent or service to their lord. However they were not forbidden from owner ship of land. By the 11th and 12th centuries it was more frequently documented that a serf was often a small holder in lands enough to have a degree of self-reliance and there by the ability to make a earning of their own from any surplus that they may reap. However our sources and documentation on the potential power a peasant small holder may have in terms of hiring his own workers are space, we know of their existence but are sorely lacking in the one factor that could make them rivals to their lords; manpower. This can serve as a reflection to an element of the records being bias towards maintaining a social view of hierarchy that was potentially not quite as uniform.

Indeed this notion is key in shining light onto the deeper, beginning with the ‘workers’ in this system; it is no surprise ‘Labortones’ built up the vast majority of society thus it seems obvious that have many divisions are bound to exist among them that lead into a ‘class’ system within this. This section of society also where far from the commonly believed slave class who toiled in the dirt that the mainstream have come to peg them as. Firstly we can see that an artisan would have much more of a status in their communities over that of an unskilled worker, n example would be butchers, tailors and blacksmiths (Smith being a general term applied to many artisan professions). These individuals would often not be a simple ‘worker’ but rather a business owner in their own right, they were not the employee’s in the conventional sense of the age in having a master. For their skills they could hold great sway in local circles, even to the extent that their so called betters would look to them to fulfill their specialist needs. Subsequently making them a none expendable part of daily life in a community being key for passing on knowledge to apprentice successors and supply of their goods. The rise of the power of these types of working men and women also can be attributed or at least aided by the rise in urbanization that flourished in this period. Their services in a town made their potential earning all the more lucrative, benefiting from serving locals as well as travelers passing though. This lead to a social group that relied on working for their living yet could claim a higher level of sway then in previous ages, still remaining in the status of a ‘Labortone’ but using the so called lowly rank to their benefit. However as noted by Brooke the status of a tradesman was a fickle matter. Records make it clear that there was an element of distrust to tradesmen, as illustrated in both law and taxation records, the rapidly expanding industry was something that the powers that be desperately scrambled to regulate. The upper classes had little faith in the honestly the peasant class leading to hash penalties should any glimmer of fraud be detected or the regulations imposed on their craft be broken.

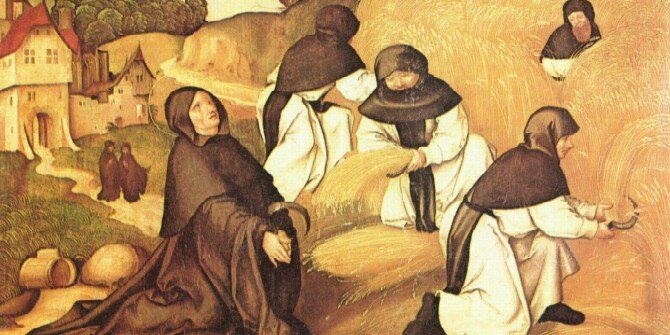

A 13th-century French representation of the tripartite social order.

Oratores ("those who pray"), Bellatores ("those who fight"), and Laboratores ("those who work").

‘Bellatones’ are shrouded in the romantic legend. It is the estate that many embellish with chivalric values, noble titles and having fought wars as well as crusades. However it is also an area of society dogged by political strife throughout the continent. This estate covered men ranging from King to knight, largely encompassing nobility. The duty of the ‘Bellatones’ can be felt in the secular and political spheres. As mentioned previously there was a stress on one’s birth into a role as designed by God, therefore bringing with it a heavy sense of Christian duty. However there was also an ingrained idea of familial duty that debatably drove the members of this estate more so then even the looming aspects of religion. Loyalty in general was a virtue drummed into the elite, being a group that was entitled to receive it but also to pay. Their social status was paramount, should they fail in their duties it stood to scar their lands, associates and authority. In a dog eat dog world there was no mercy for a slip up. As stated by well the respected historian Marc Bloch, The position of the warrior in the medieval mind was a place that carried pride as an essential element, even more so in the case of knights. He goes on to argue that to many it was so much more than an occasional service to pay in arms, it was a rather felt to be their entire purpose.

The importance of oaths and by extension the concept of being a vassal was integral for this second estate. It can be seen as both a social and legal construct, by which they could gain their power and dues from action but also become subject to various restrictions and expectations to those they had pledged their loyalty to. In the middle ages a man’s word was very serious, particularly when we view it in the context of knighthood. Knighthood itself was governed by social expectations and duties across the spectrum of interaction. Military service was expanded on to build it as far more respectful and virtuous. An oath was sworn beyond service in arms, other factors that where stressed in the very ceremony of dubbing where protection of the women, children and the poor. Along with the expectation to fight for and defend their faith, which would be stressed all the more as the crusades became a frequent occurrence over the age. The ideas of those who fought where also overwhelmingly concerned with social aspects. Largely the more regarded of this estate where of noble origin, the lower of the noble classes even using this a same method to further themselves. This being a saving grace for those born as the second sons (Therefore not to inherit land or wealth upon the passing of their father.) This is however not to say that those who fought where entirely of noble birth. We are fully aware of the peasants that played their parts in armies. In fact see a social barrier from their role in war. A villein would be brought into the battlefield by their lord in order to build their numbers (what could be considered a quota). Their position was typically an unskilled one such as a pikemen or archers and their grim fate similar to sending in the cannon fodder. This shows two important factors to consider within the question of the three estates as a social construct. To put it simply; these peasant soldiers had nowhere near the respect a noble or knight would have had enjoyed. They may have fought but there was no thought of them being members of the second estate. By this we can interpret that the participation in war alone did not the ‘warrior classes’. It was equally an estate built from a man’s professional skill and ability to pursue it.

Although the ‘Oratones’ where viewed as the top of this chain their power varies in its potency throughout the middle ages. Culturally they had a level of respect gained from the belief that they, the clergy, where the closest to God on earth. But cross overs again gradually begin to become apparent, making this estate perhaps the victim of the most social fluctuation. Boundaries where constantly being tampered with in both social and political spheres by members of the religious orders themselves. This fragmentation and stepping outside their station would come under fire from internal and external critique. The debates concerning just how much sway these men and women of god could rightly hold would shape the face not only this so called top ranking estate but also the impact they would have on the rest of society at large.

One of the clearest examples we can draw upon for social strife is that of the monastic orders. These three centuries would see a surge in the growth of monasticism but symptomatically an increasing debate into just what was a truly monastic existence. In essence the life of a monk or nun was that of isolation from society and devotion to God while living a provincial life. However this ideology is far harder than the simplicity it implies. Interaction with the wider world was something that could vary in the monastic houses, a main criticism of some orders was indeed their degree of interaction with the outside world. Many monasteries where accused of breaking key beliefs in their supposed life style by the action of gaining payment from lay members for tasks such as prayer for their own or departed family members souls. This in addition to accepting the gifts of land and building extensions and even as far as becoming payed tutors to the sons of noble men. This meant that their social dealings where painfully undeniable to anyone with a slightly critical mind, however it was not viewed as largely abhorrent. The view of monks cheating laity out of wealth for ulterior means is one that we can blame on the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. The trouble came from insider, hence the rise of differing orders. It is also foolish to believe that one could entirely turn away from any interaction from the outside world. In a environment that was becoming ever more urbanized communication was needed more so then ever to reach out to lay people for something as vital as supplies. Though most could boast self-sufficiency it was impossible to really on in times of a poor harvest or thee location itself lacking the skill and means to produce any goods they may need just to live. Therefore they was some need to keep good contacts with communities around them as well as accepting gifts in a manner that does not abuse their values. It is also true that they are recorded in some cases to benefit the area around them in what they may be able to provide other than religious matters. Such as selling surplus crops, beer and textiles.

Cistercians at work in a detail from the Life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux (cropped), by Jörg Breu the Elder (1500), Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

For obvious reasons no individual was born into a religious role. Therefore a person had to make the transition from one estate to another. This movement was not without challenge due to the commitment it required, their struggle often lends to their favour as a religious figure. In the case of Christina of Markyate, a wealthy woman expected to marry well there is a clear social barrier for her rejecting betrothal. Christina fought hard for her escape from the social conventions of marriage and family to act on her faith, Pushed by claims of divine intervention. The reasoning is for her family’s insistence can possibly be linked to family lineage (We have no record of siblings). The portrayal of Christina reads as a saintly history. Claiming she even goes as far to threaten to burn her hands. (Likely representative of making herself unable to sign a contract or physically make the marriage vow). She would succeed in her religious endeavors, making an example of her struggle. However this is not to say that she alone made the passage to the estate any easier. The line between the first estate and the two lower ones would remain difficult to cross.

It therefore can be seen that the three estates can in many ways help us understand medieval society, however it is not in the case that may be seen at face value. The Estates and just how they could help or hinder a person where heatedly debated at the time and it continues to be the case now. The medieval world is so coloured by the reflections of each century since that it has swerved the true context. The only way we can hope to glimpse a true illustration of their thoughts is to approach the material as objectively as possible without the legal labels that cling to the social aspects.