National Alcohol Prohibition: A failed experiment?

Several temperance movements who campaigned for national alcohol prohibition strengthened their view by arguing that national alcohol prohibition would create significant economic benefits. These benefits would be achieved by diminishing illness, absenteeism, accidents, and soaring consumer goods expenditure. Nevertheless, was this the case for the United States? Why is national alcohol prohibition, often called a failed experiment?

When, in 1917, the United States joined world war one, the government had temporarily banned liquor with the implementation of the 18th Amendment. This was called the wartime prohibition. The reason the government banned liquor production was that it was more important during wartime to use grain for food and not for alcohol-containing products.

Shortly after the war in 1919, temperance movements in the society saw the chance to ban alcohol from the constitution. Temperance movements like the Anti Saloon League thought that alcohol created the greatest threat to public health. In the early 20th century, the United States was a significant consumer of ethanol. The United States had the highest consumption rate in annual ethanol at 2.6 gallons per capita of the drinking-age. Even during the Civil War, consumption was not that high. These were the temperance movements' main arguments to start campaigning for national alcohol prohibition, besides the significant economic benefits national alcohol prohibition could entail.

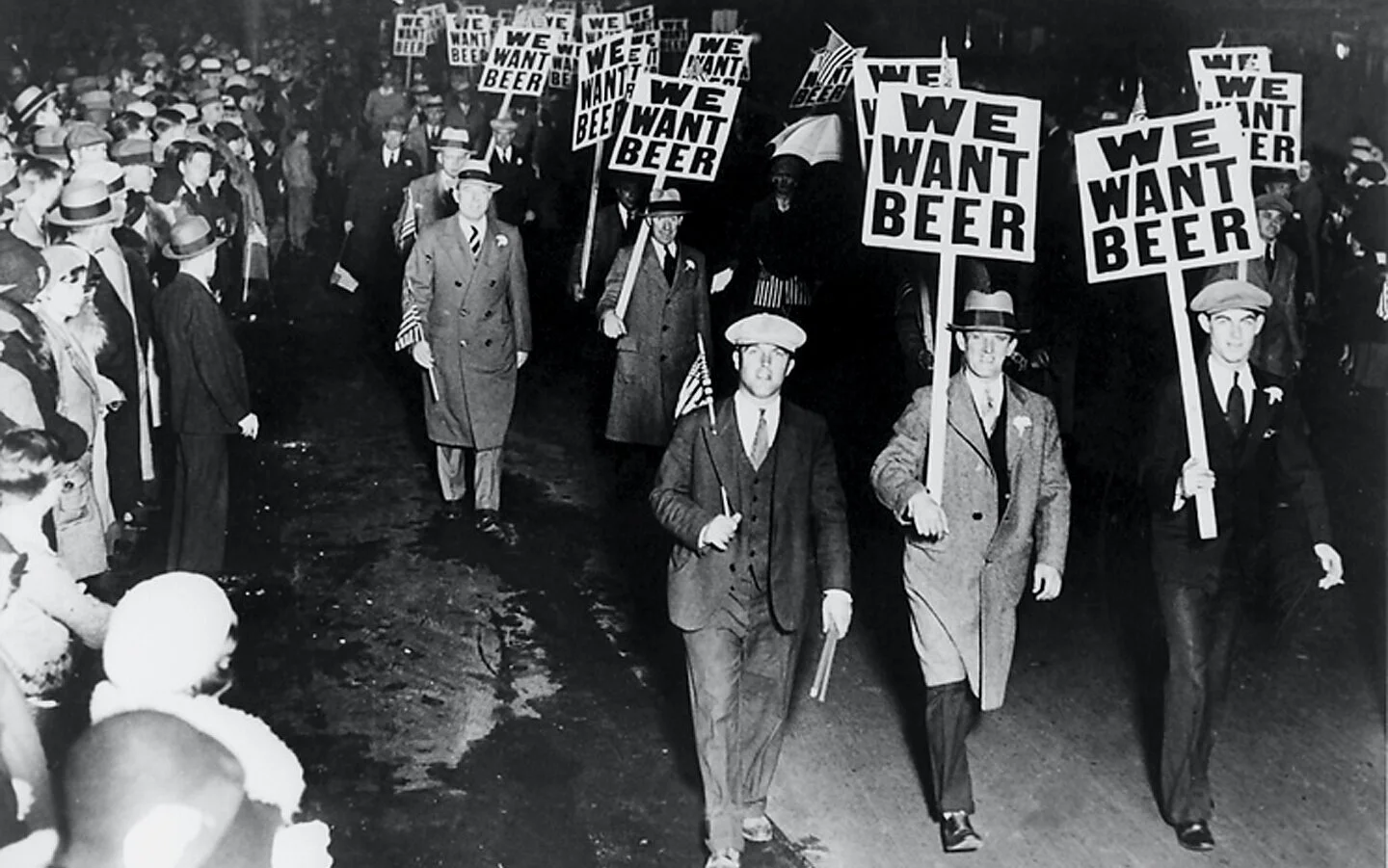

The national alcohol prohibition campaigns separated the country into the 'wets' and 'drys'. The 'drys' disapproved of drinking and considered saloons and other alcohol drinking locations corrupt. Conversely, the 'wets' wanted the state uninvolved in morality discussions. Drinkers, in general, were not portrayed in favourable terms. Most daily newspapers and family magazines did not even accept liquor ads.

The 18th Amendment, however, was not strong enough to start a national alcohol prohibition. But, with the passage of the Volstead Act, ratification of the Amendment was achieved by a two-thirds majority in Congress. National alcohol prohibition went officially into effect on January 17, 1920. It was the government’s attempt to outlaw the production, sale, shipments of alcohol and intoxicating alcoholic beverages across the country. "Intoxicating" was defined as any drink containing more than 0.5% alcohol. Whereby almost all alcoholic drinks were forbidden. The Volstead Act, however, was not entirely prohibiting alcohol. The Act did not forbid alcohol use or possession legally, but this was not always the case.

After national alcohol prohibition went into effect, most distilleries, breweries, and wineries closed their doors persistently. The liquor industry came to an end. Other industries knew that a ban on alcohol would decrease the spending on alcohol-containing products. This would automatically lead to an increase in spending on household goods and appliances. Which, in turn, would be very beneficial for the industries that supported national alcohol prohibition. The government probably knew that national alcohol prohibition would have ended the liquor industry, which might have been their intention.

However, national alcohol prohibition ended the legal liquor industry and created another more severe problem. Most crime gangs did not hesitate to claim these closed breweries, distilleries, and wineries after national alcohol prohibition went into effect. Crime gangs saw the high profits they could achieve with the illegal production and sale of alcohol in the black markets. These crime gangs strengthen themselves by working together and by responding to people's demands. However, the cooperation between the crime gangs ended with the start of the beer wars. Gangs became rivals after territorial misunderstandings, and gang murders increased. Besides just gang members, police officers, and civilians were also victims of these beer wars.

It was not an easy task for the government to prevent the beer wars and emergent black markets because the government's enforcement was deprived. The government could never have predicted the rise of organized crime due to national alcohol prohibition. Therefore, the government's reaction to make new efficient laws to control these beer wars and black markets came too late. Because of the increase in violence and crime, the support for national alcohol prohibition among the people decreased drastically. Urbanized cities like Chicago and New York, where criminal gangs were controlling most of the businesses, were like warzones. Homicides increased dramatically, especially in Chicago.

One of the main objectives of national alcohol prohibition was to create a new generation who had no alcohol consumption habits. In the first place, it looked like national alcohol prohibition was doing well to protect the youth from alcohol. Most of the saloons that sold alcoholic beverages were closed after national alcohol prohibition went into effect. However, this positive progress in protecting the youth came to an end after the speakeasies opened. These illegal drinking locations were possible due to the rise of the black market. The gangs who were active on the black market produced and sold alcoholic beverages to these illegal locations, which were attended by both men and women.

Even though national alcohol prohibition had good intentions, it also had a lot of bad consequences. The main consequence was the creation of the black market, which led to many economic and social consequences.

The government struggled to control the upcoming black market of alcohol and had a lack of income, which made it challenging to create new rules to enforce national alcohol prohibition. Supporters of national alcohol prohibition thought that the loss of tax revenues in the liquor industry would be compensated with the profits in other industries, but this was not the case. The liquor industry suffered enormously from national alcohol prohibition which cost many jobs. The other industries did not compensate most of these lost jobs.

The second major consequence was the rise of the black market. Crime gangs murdered each other to get control of the black market, and the increase in alcohol consumption resulted in a high number of deaths. National alcohol prohibition created new public drinkers who were women and college youth. So generally, it created more drinkers. In the end, deaths during national alcohol prohibition did not decrease enough to say that public health benefits were reached at an acceptable social cost.

Although the Act was difficult to enforce and not always transparent, national alcohol prohibition did last for more than a decade, until December 5, 1933. The American people thought that national alcohol prohibition was encroaching on their freedoms. Disillusionment reached an all-time high during the Great Depression, which eventually led to the development of a repeal movement. The implementation of the 21st Amendment allowed every state to implement its own laws regarding alcohol. National alcohol prohibition came finally to an end with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the 32nd president of the United States.

Worldhisstory Instagram

References:

Asbridge, M., & Weerasinghe, S. (2009). Homicide in Chicago from 1890 to 1930: Prohibition and its impact on alcohol‐and non‐alcohol‐related homicides. Addiction, 104(3), 355-364.

Blocker Jr, J. S. (2006). Did prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation. American journal of public health, 96(2), 233-243.

Dills, A. K., Jacobson, M., & Miron, J. A. (2005). The effect of alcohol prohibition on alcohol consumption: evidence from drunkenness arrests. Economics Letters, 86(2), 279-284.

Dills, A. K., & Miron, J. A. (2004). Alcohol prohibition and cirrhosis. American Law and Economics Review, 6(2), 285-318.

Hall, W. (2010). What are the policy lessons of National Alcohol Prohibition in the United States, 1920–1933? Addiction, 105(7), 1164-1173.

History.com Editors. (2020, 14 januari). Prohibition. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/prohibition

Landesco, J. (1932). Prohibition and crime. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 163(1), 120-129.

Levine, H. G., & Reinarman, C. (1991). From prohibition to regulation: lessons from alcohol policy for drug policy. The Milbank Quarterly, 461-494

Miron, J. A., & Zwiebel, J. (1991). Alcohol consumption during prohibition (0898-2937). Retrieved from

Petkus Jr, E. (2008). Value-Chain Analysis Of Prohibition In The United States, 1920-1933: A Historical Case Study In Marketing. Journal of Business Case Studies (JBCS), 4(8), 35-42.

Sybrandi, H. M. (2018). Een illusie armer. Veranderde argumenten in de strijd omtrent de Amerikaanse drooglegging (1919 19330) (Bachelor's thesis).

Thornton, M. (1991). Cato institute policy analysis no. 157: Alcohol prohibition was a failure. Washington DC: Cato Institute.

Tyrrell, I. (1997). The US prohibition experiment: Myths, history and implications: (alcoholism and drug addiction). Addiction, 92(11), 1405-9. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/199630189?accountid=27889

Welskopp, T. (2013). Prohibition in the United States: The German America experience, 1919-1933. Bulletin of the GHI, 53, 31-53.